Unsophisticated and unsuited

27 August 2015 - by Paul Hamer

In the early 1900s, and in spite of the principles of the White Australia policy, Australia was forced to treat Māori crossing the Tasman in largely the same way as Pākehā New Zealanders. This served, first, to encourage New Zealand to federate and, secondly, to maintain healthy trans-Tasman diplomatic relations.

But extending uninhibited rights of entry to Pacific Island (and Asian) New Zealanders long remained a bridge too far for Australia. This was a cause of increasing tension with New Zealand, which had embraced closer ties with the Pacific and had, from the 1960s, allowed the immigration of thousands of Pacific Islanders.

As late as 1971, the Australian Cabinet agreed that Pacific Islanders were too 'unsophisticated' and 'unsuited' to settle freely in Australia. The election of the Whitlam Government in 1972, however, led to the abandonment of this and other final vestiges of the White Australia policy.

But in the four decades since Australia has progressively curtailed the rights of New Zealand migrants entering the country. There is good cause to believe that Australian dissatisfaction with New Zealand's more liberal rules of entry for Pacific Island migrants is one of the reasons behind this.

This talk was delivered on August 5th as part of the series on conflict presented jointly during 2015 by the National Library of New Zealand and Victoria University of Wellington. It is an abbreviated version of an article originally published in Political Science, 66(2), 2014.

Paul Hamer is a Wellington historian and a research associate at Victoria University's School of Māori Studies, Te Kawa a Māui. He is studying for a PhD on aspects of Māori migration to Australia.

“A White Australia

Maoris not to be tested.

Press Association - by Telegraph - Copyright.

Melbourne, March 2.

(Received March 2, at 11.50 pm)

Mr Reid, the Federal Premier, has decided to issue instructions not apply the language test to Maoris. A report on the recent case called for by the External Affairs Department shows that both Maoris were asked to pass the test in English, but did not do so. Mr Reid, in answer to the question, “what was to be the general….”

An extract of A White Australia, from the Otago Daily Times, 3 March 1905.

White Australia

One of the foundation stones of 'White Australia' in 1901 was the Commonwealth's exclusion, along with other so-called 'coloured' peoples, of Pacific Islanders. The Australian colonies had hoped that New Zealand might join their federation, but New Zealand already had a different relationship with the Pacific. Not only had it annexed Pacific territories, but its own indigenous population was Polynesian and enjoyed greater comparative rights than Australian Aboriginals. For many decades after 1901, therefore, the close relationship between Australia and New Zealand - based on the shared British heritage of their settler populations - was complicated by both the status of Māori in New Zealand society and New Zealand's growing links with the Pacific.

This is an account of the political difficulties arising from New Zealand's relative embrace of the Pacific, on the one hand, and Australia's status as what has been called 'the reluctant Pacific nation', on the other.

Pre-1940s background

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Polynesians were generally highly regarded by British officials in Australia, who were perhaps influenced by the romantic notions of 18th century explorers, some of whom had likened Polynesians to ancient Greeks, or even Greek gods.

Over time, however, a divide began to open up in British colonial attitudes towards Māori, on the one hand, and people from the islands, on the other. In late 19th-century New Zealand, Pākehā New Zealanders began to develop a form of nationalism based on the myths of mutual respect between Māori and Pākehā forged on the colonial battlefields. Some even proclaimed a degree of kinship with Māori. In Australia, by contrast, Queensland sugar farmers began in the early 1860s importing indentured Melanesian workers to cut cane, and by 1901 Queensland had a Pacific Islander population of over 9,000. While almost all came from the New Hebrides and the Solomon Islands, they tended to be referred to simply as 'Polynesians'. From the 1880s, and the advent of Australia's own nationalism based largely on the ideal of a White Australia, their presence became deeply resented. Pacific Islanders were excluded from membership of the new Australian Workers' Union in the mid-1890s, whereas Māori were not.

An early action of the new Commonwealth Government, therefore, was to pass the Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901, which was designed to remove Melanesian people from Australia. The legislation defined 'Pacific Island Labourer' as including 'all natives not of European extraction of any island except the islands of New Zealand situated in the Pacific Ocean beyond the Commonwealth'. The Māori exemption from this racial discrimination was generally repeated in other legislation, such as the Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902 and the Naturalization Act 1903.

Before the wording of the exemption for Māori in the Franchise Act had been finalised, one Australian senator expressed concern that enfranchising New Zealand's 'natives' could have unintended consequences. Queensland Senator James Stewart feared that it might require Australia to extend the vote to the native peoples of any islands in the Pacific New Zealand already administered (such as the Cook Islands) or later managed to add to its territory (as seemed possible at the time with Fiji). As Stewart put it:

“New Zealand wants to become a sort of suzerain over all the islands in the Pacific. If she succeeds, and if she subsequently joins the Federation… the question will arise whether the aboriginals of her island possessions have the same right to the franchise in Australia as the New Zealand aboriginals have. I am not prepared to admit that proposition. We are quite willing to admit New Zealand, into partnership with us, together with the Maoris, but we should object to the inhabitants of the Pacific Islands being admitted to the franchise.”

The Bill's wording was amended to meet Stewart's concern. His position revealed an early Australian antipathy towards New Zealand's relationship with the Pacific, and an unwillingness to contemplate Pacific Islanders gaining equal rights with other members of the Commonwealth through that association with New Zealand.

After complaints from the New Zealand Government over the exclusion of two Māori shearers in 1905, the Australian Government issued an edict to its customs officers that henceforth Māori were to be admitted freely to the Commonwealth without having to undergo the dictation test prescribed by the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901. But Pacific Islanders remained subject to the test, under which they could be asked to write out a passage dictated in any European language. At the same time, Australia began to deport thousands of Melanesians from 1906.

The push for equal treatment, 1948-1973

Let's move forward to 1948. In April that year, the Tongan wife and two daughters of a British resident of Perth, Stewart Carrick, were ordered to leave Australia by Immigration Minister Arthur Calwell, after being declared aliens under the Immigration Restriction Act. Calwell was indeed a stickler for the maintenance of a White Australia, and after the war had been busily deporting the Asian husbands and wives of white Australians. Shortly after ruling on Mrs Carrick, Calwell was asked in Parliament whether he would allow a Māori ex-serviceman who had married an Australian woman to settle in Australia. Calwell told the House that 'Within the meaning of the Immigration Act, they [Māori and Tongans] are regarded as the same people, and under existing law and practice, such people will not be permitted to settle permanently in Australia'.

Calwell's statement triggered outrage in New Zealand. Prime Minister Peter Fraser released a statement asserting that 'any hint of discrimination, against our Maori fellow citizens would be indignantly and bitterly resented as an unforgivable insult to our country and every one of us'. Inevitably, Calwell backed down, and Fraser was assured that free Māori entry to Australia was under no threat.

Calwell's clarification appeased New Zealand but rather laid bare the Māori exception that had existed quietly for decades. This was recognised by the Daily Telegraph in Sydney, which wrote 'there is now no logical answer to pleas from Australian girls married to negroes, Indonesians, and Malays, Australian men married to Chinese girls, or from any of the Polynesians of the Pacific who might ask for admission on the grounds that we have already extended hospitality to their racial brothers'.

Indeed, the sense of injustice over the exclusion of Mrs Carrick prompted the editor of the Australian publication Pacific Islands Monthly to write to Fraser asking that he put the same case to the Australian Government on behalf of Samoans and Cook Islanders as he had just done for Māori, since New Zealand administered those two territories and their people were fellow Polynesians. Fraser replied that such matters did not appear to be ones 'with which the New Zealand Government could concern itself'.

Pacific Islands Monthly published Fraser's reply and remarked that 'It will certainly be a matter of interest to the people of Western Samoa and the Cook Islands - both of which are administered as territories of New Zealand - to learn that their exclusion from Australia is not a matter with which the New Zealand Government will concern itself'. This agitating may have had some effect: in early 1950 the newly elected National Government was reported to have intended to discuss the issue with the Australians.

But progress was slow and, if the New Zealand Government did raise the matter, it is unlikely to have done so forcefully. In April 1956 the Australian Immigration Department issued a policy directive that Cook Islanders were not eligible to enter Australia. This explained that: “The reason for the distinction between Maoris and Cook Islanders, despite their common ancestry, is that the latter unlike the Maoris, have not as a people had a long and continuous membership of a predominantly European community and could not be expected to assimilate in Australia easily.”

In 1958 Cook Islander Marjorie Crocombe, an anthropologist (and wife of the Pacific scholar Ron Crocombe), was required by the Australian Trade Commission staff in Auckland to undergo a full medical examination and purchase a return ticket prior to a visit to Australia. As she explained, 'When I asked why these things were required, the Australian trade commission staff said it was because “Cook Islanders have a low standard of living” and that Cook Islanders “may not know how to behave” in Australia'.

The New Zealand Government eventually took a firmer stance on the matter after an incident that had echoes of the denial of entry to the two Māori shearers in 1905. In February 1965, a 21-year-old Cook Island man named Nooroa Tuaiti sailed from New Zealand to Sydney on the Oriental Queen with a view to finding work there. For a range of reasons, he was not allowed to leave the ship at Darling Harbour: according to Australian Immigration authorities, he had too little cash and no return fare, no passport, and had only been in New Zealand for three years. He had not thought he needed a passport, but as the Australian Trade Commissioner in Auckland put it, 'This man should have taken his birth certificate to the internal affairs people, been issued with a passport and have brought it to me' for consideration.

It seems that there was another factor in the denial of entry to Tuaiti: his appearance and skin colour. The immigration officer had decided that Tuaiti 'appeared to be fully Melanesian (and therefore not readily identifiable with Cook Island Maoris)'. Immigration officials also thought it 'not unreasonable' that any Cook Islanders arriving to live in Australia should first have had some period of living in New Zealand 'to enable them to have become identified with the European way of life'. Evidently, they regarded Tuaiti's '2 or 3 years' as insufficient for this to have occurred.

News of Tuaiti's exclusion created a furore in New Zealand. Students, MPs, and even Ministers voiced opposition. By May 1965 the Australian Department of Immigration had conceded that, since New Zealand had granted 'full status upon the natives of the Cook Islands, Niue Island and Tokelau Island', then Australia should not place them in the same category as Papuans, who had no free entry to Australia. The department proposed that the 1920 agreement between the two countries on passport-free travel for natural-born British subjects be updated by the reintroduction of passports for all travellers and that 'we might consider including in the “Maori” category those natives of the Cook Islands, and Niue and Tokelau Islands who have first been resident in New Zealand for a period of say three years'.

Australian officials may have seen this as a significant concession, but their New Zealand counterparts did not accept it, arguing that there should be no separate standard applied to New Zealand citizens from its island territories (or Asia, for that matter).

Eventually, Australian Immigration officials put their proposals for liberalising the entry rules to their Minister, Billy Snedden. In April 1968 he took the matter to Cabinet. He ventured that there was no indication that Pacific Islanders would migrate on to Australia from New Zealand if given the same freedom Māori had enjoyed. He recommended that Asians who were New Zealand citizens or British subjects resident in New Zealand be allowed to enter Australia without restriction, if they held passports, and that New Zealand citizens from its island territories should be allowed in on the same basis as Māori. But others within the Australian Government were not minded to be so liberal. The Prime Minister's Department noted what they saw as:

“problems in the proposal to allow Islanders from New Zealand's Island Territories to be placed on the same footing as Maoris in respect of entry to Australia… If only a few Islanders were to come to Australia it would be likely that they would encourage others to follow. In such a situation it would be difficult to justify the free entry of Islanders from New Zealand territories when we do not allow this for Papuans and New Guineans.”

Cabinet considered the paper on 17 April 1968. It felt that making the changes (with respect to both Asians and Pacific Islanders) 'could carry implications for established immigration policy which it considered should be avoided', and asked 'that the proposal be regarded as indefinitely deferred'.

Despite this setback, the New Zealand Government persisted. In 1969 the Minister of Immigration, Tom Shand, wrote to Snedden and expressed New Zealand's willingness to remove all barriers to Australian citizens' free entry to New Zealand, with travellers to be asked for proof of citizenship on arrival in case of any concern that they were not citizens. Nothing came of this approach, however.

The matter was taken up again in September 1970 by Shand's successor, Jack Marshall. He made the case to his Australian counterpart that the world had changed since the 1920 agreement on trans-Tasman travel, and it was time the Australian policy was 'modified to conform with the trend of public opinion'.

Eventually, the matter was taken to Cabinet by Australian Immigration Minister Jim Forbes in May 1971. He set out five arguments in favour of making the change New Zealand was requesting: the special relationship between the two countries; averting charges of Australian racial discrimination; non-European Australians having better access to New Zealand; the fact that 'for 66 years the Maoris (much more numerous than other non-European New Zealanders) have been free to come here and this has not caused any significant migration to or problems for Australia'; and the further fact 'Cook Islanders are of the same ethnic origin as Maoris and there are practical difficulties in discriminating between them'.

Forbes then set out three points against any changes: 'Papuans (who are legally Australian citizens) could be aroused to seek similar freedom to settle here'; 'New Zealand's substantial and increasing numbers of Pacific Islanders (settling in New Zealand at the rate of some 2,000 per annum) are unsophisticated and would be quite unsuited to settlement in Australia; many are tending to congregate in the industrial suburbs of Auckland, with resultant social problems'; and Australia's commitment would be an open one and New Zealand could potentially 'further relax its immigration policy towards non-Europeans'. Forbes concluded that the points against 'decisively outweigh those in favour, even if one accepts that the numbers likely to settle here are not great'.

Accordingly, on 25 May 1971 Cabinet decided 'that existing controls over the entry to Australia on non-European New Zealanders should be maintained'.

On 29 June 1971 Marshall made the announcement that his Government would unilaterally remove any racial restrictions applying to Australian citizens entering New Zealand. The Australian Financial Review covered these developments on its front page of 6 August 1971. It claimed that:

“Somewhere in the Australian Cabinet runs a hard streak of racial bigotry. While our restrictive immigration policy has been a constant source of friction with Asian countries, Cabinet has now made a decision on entry policy which Australia's closest ally, New Zealand, regards as nothing more than an insult.”

Australian officials continued to note news stories that perhaps reflected the underlying sentiments behind their Ministers' position. The Prime Minister's Department clipped a September 1971 story from the Australian headed 'Polynesians: city influx causes slums' which claimed that 'The Polynesians, mainly Samoans and Cook Islanders, speak little English and are unable to cope with the pressures of urban life' in New Zealand.

Renewed restrictions after 1973

After Labor swept to power in Australia in December 1972, the new Immigration Minister, Al Grassby, made it clear that he would do away with the restrictions as a priority. Gough Whitlam and Norman Kirk issued a joint communiqué on 22 January 1973 providing for passport-free travel between the two countries for all citizens of Australia and New Zealand as well as citizens of other Commonwealth countries with permanent residency rights in either country. This announcement of the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement essentially represents the high-water mark in the history of access to and rights in Australia for New Zealand citizens.

At the time, Kirk was sufficiently aware of Australian sensitivities to allay 'fears that the change in policy would lead to a flood of islanders to Australia. Only about 37,000 were involved', he explained, and 'most had roots in New Zealand, and an affinity for Polynesian society'. It is clear, however, that Australia felt somewhat exposed by the new open door, with occasional murmurings from Canberra about Australia's lack of control over who was permitted to enter New Zealand.

The comparatively straightforward entry of Pacific Islanders to New Zealand was evidently part of the Australian concern. In January 1975 11 Pacific Islanders were being held by Australia for deportation, including one Tongan who had entered the country by 'posing as a Maori'. In 1975 Pacific Island church leaders in Sydney complained of midnight house raids of suspected illegal immigrants. A decade later, a Tongan man in Canberra took proceedings against the Department of Immigration for what his lawyer described as the discriminatory enforcement of immigration law against Pacific Islanders.

Australian Immigration Minister, Ian McPhee, announced Australia's requirement for passports for trans-Tasman travel on the eve of Anzac Day in 1981, ostensibly to control drug traffickers and the like. New Zealand's Minister of Foreign Affairs, Brian Talboys, denied that the Australian concerns had any 'real basis'. A degree of scepticism about the official reason existed. The Canberra Times decried the 'stupid' new policy, and noted that 'the suspicion is abroad in Canberra and Wellington that Australia is trying to keep out or at least reduce the numbers of Maoris and Pacific islanders coming into Australia'.

The numbers of Pacific Islander migrants from New Zealand remained relatively low in Australia at the time. But it was perhaps more the change in the nature of New Zealand immigrants that unsettled the Australians. Aussie Malcolm, now an immigration consultant, was responsible for New Zealand Immigration as Parliamentary Under Secretary, Associate Minister, or Minister from 1977 to 1984. In that capacity he attended, as a courtesy, the regular summits of Australia's state immigration ministers. He explained in an interview in April 2013 that 'it was in that environment that I became aware that Australia did indeed see the Trans-Tasman Agreement in terms of racial issues':

“[When these] rather large brown people who didn't speak English that well and came from Samoa and Tonga… started crossing the border saying 'I'm a Kiwi' it did certainly blow the Aussies away. And that's what led in the first instance to the demand for passports, because they simply didn't believe it. They had a - what can I call it - they had a stereotype in their head that a Kiwi was a white guy like an Aussie. And when New Zealand started producing these Polynesians, who weren't like Aussies, but who were New Zealanders, that rattled them. No two ways about it.”

Malcolm recalled that the Australian state ministers would tell him, informally, that they had no problem with white New Zealanders settling in Australia, but that Māori and Polynesians represented a significant problem to them. Unsurprisingly, the Privy Council's July 1981 ruling that Western Samoans born between 1924 and 1949 and their immediate descendants had the right of New Zealand citizenship caused some alarm in Australia, and the annual intake by New Zealand since the 1960s, under a quota system, of at least 1,000 Western Samoans as permanent residents has clearly caused Australia some disquiet, as we shall see.

In 1994 the Australian Government introduced the Special Category Visa (SCV) for arriving New Zealanders. The Liberal Opposition's immigration spokesman, Philip Ruddock, remarked at the time that:

“I would not like to think that New Zealanders, in terms of the administration of what is, in fact, the common border, digressed so widely from our own criteria for determining entry that backdoor migration to Australia was possible for classes of people who would not access Australia by first going to New Zealand and then seeking to come to Australia. It troubles me from time to time that New Zealand is in the business of structuring its migration program in a way which may put some emphasis and weighting on country of origin or race in determining entry. If that were the case, it would be of concern to me because I do regard non-discriminatory criteria as being of the utmost importance.”

Ruddock became Minister of Immigration upon the election of the Howard Government in 1996. By the end of the decade, concern was mounting about the proportion of New Zealand migrants to Australia who were born in third countries, which had climbed from around 12 per cent in 1990-91 to 30.0 per cent in 1999-2000. The press reported that 'The Federal Government is under pressure to crack down on Polynesians and Asians using New Zealand's migration program as a stepping stone into Australia'. Ruddock stated that Canberra was keeping an eye on the proportion of New Zealand migrants born in third countries but that it was not yet a concern.

In September 2000, however, the public tone changed when New Zealand Immigration Minister Lianne Dalziel announced an amnesty for overstayers who had lived in New Zealand for some time and were well settled with jobs and families. A large proportion of those likely to benefit were Pacific Islanders. Ruddock now suggested that the increasing numbers of New Zealand migrants to Australia born in third countries did 'tend to suggest back-door migration'. He stressed that those to be granted amnesty had not met New Zealand selection criteria for immigration and would be able to go on and enter Australia.

To make matters worse, in Ruddock's eyes, Dalziel announced shortly afterwards that the government was planning to replace various work-permit schemes and quota arrangements with Pacific nations with what became known as the 'Pacific Access Category', under which 1,500 Pacific Islanders would be able to enter New Zealand each year. Ruddock expressed 'disquiet' over the plans, noting the contrast between New Zealand's special arrangements with island states and Australia's 'non-discriminatory' immigration policies. His spokesman added in November 2000 that New Zealand's arrangements with several South Pacific countries allowed those unable to meet Australia's immigration criteria to enter the country via New Zealand, after first obtaining New Zealand citizenship.

The notion of 'back-door' migration, the amnesty, and the proposed new access category for Pacific Islanders also attracted the attention of the Australian Opposition. Labor MP Martin Ferguson asked Ruddock in Parliament on 27 November how much longer Australia would tolerate New Zealand 'making its own migration decisions irrespective of their consequences for Australian taxpayers'. Ruddock replied that changes to the current bilateral social security arrangements between the two countries were in train.

Indeed, at the same time as the over-stayer amnesty and new Pacific migrant intake were causing tension, New Zealand and Australia were renegotiating their bilateral social security agreement. Australia wanted New Zealand to reimburse Australia considerably more money for the welfare costs of New Zealanders resident in Australia, and New Zealand officials felt it was clear that unless Australia was appeased it would either severely restrict New Zealanders' access to social security or possibly restrict free entry to Australia to the New Zealand-born only, and thus - officials noted - exclude groups 'such as Pacific Island migrants'.

The amnesty probably hardened Australia's resolve to take action. Ruddock indicated at the end of September 2000 that New Zealand's offer to overstayers meant that Australia might consider revisiting the free entry provisions of the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement. This was, of course, already very much on the cards. As it transpired, on 26 February 2001 the Howard Government announced the new national measures under which newly migrating New Zealanders would have to apply for and receive an Australian permanent visa before being eligible for welfare payments.

New Zealand officials were conscious that certain groups would be worse affected. In November 2000 Ministry of Social Policy officials told Ministers that 'because of the occupational skill requirements in the Australian criteria, a high proportion of those losing future social security entitlements will be of Maori or Polynesian background'. Aussie Malcolm drew on his earlier impressions and commented that Australia was attempting to discourage Pacific Islanders and Māori from migrating. Asked at his joint press conference with New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark on 26 February 2001 whether Australia's new measures were designed to deter Pacific Islanders from moving to Australia, John Howard called the question 'preposterous, even offensive'.

There may, however, have been an ongoing belief among some Australian decision-makers in 2001 that Pacific Island New Zealanders were, as described in 1971, 'unsophisticated' and 'unsuited'. Coalition MP Gary Hardgrave became the Minister for Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs in November 2001, and was not in Cabinet at the time of the changes. However, he spoke candidly on Channel 9's A Current Affair programme in January 2014 on what he saw as the link between the changes and the immigration of Pacific Islanders:

“The idea of not giving them access to these benefits was to say 'Hey, don't come.' They've still come anyway. I don't think it's the back door, it's actually the front door, it's the only door. I mean you just fly across. They get no support. They get absolutely no settlement services support, they don't get any English-language training, they don't get any skills on how to be part of our society. If you think the trickle of trouble we have got right now is an issue, open the floodgates up by giving everyone the dole, it will be a dam burst.”

The reference to the lack of skills 'on how to be part of our society' was reminiscent of the Australian Trade Commission staff's reported suggestion in 1965 that Cook Islanders 'may not know how to behave' in Australia.

Ongoing Australian concern

The 2001 changes have not been the end of the matter, in that there is still a degree of Australian concern about the ease of Pacific Islanders' access to Australia via New Zealand. In May 2006, Coalition MP Cameron Thompson expressed such concern to Foreign Affairs officials:

“My query was to do with what struck me in New Zealand as rather porous borders between New Zealand and the Pacific islands. Is there any concern that people can find their way from anywhere in the Pacific islands to Australia through New Zealand? Is that an issue?… The sort of context I was looking at there was that I understand that Cook Islanders get New Zealand citizenship or something. I think that also applies to other places, whereby they get an easy accommodation with New Zealand citizenship there. Are there any concerns about that? Is there any pressure to change those arrangements as they apply in New Zealand?”

Thompson was reassured by an official that the number of Pacific Islanders automatically entitled to New Zealand citizenship was 'extremely small'. The following month, however, he asked at the same subcommittee how easy it would be for people from the Pacific, who often 'have multiple names' which can 'spawn multiple identities', to 'get a fairly easy right of entry into New Zealand and… wind up in Australia'. They could then end up 'seeking welfare payments', which Thompson suggested 'could result in welfare fraud'.

Others also continue to view Pacific Island immigrants negatively. In 2010 former Treasury Secretary and National Party Senator for Queensland John Stone complained in Quadrant that, “Cook Islanders, Niueans and Tokelauans have enjoyed New Zealand citizenship since 1949. In addition to these Pacific Islanders, New Zealand provides for 1500 people each year from Samoa, Kiribati, Tuvalu and Tonga to settle in New Zealand. Once they have resided there for five years, and have not committed any serious crime (more precisely, not been caught doing so), they too are eligible for citizenship. They are then free to enter and remain in Australia. Today, most of our Pacific Islander residents are not here through our formal immigration programs (under which most of them would simply not qualify), but via the back door which the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement now constitutes.”

In 2012 demographer Bob Birrell told Radio Australia's Pacific Beat programme that the migration of Pacific Islanders from New Zealand was an issue all right, and particularly in Sydney and south east Queensland - they're concerned about it… I do think there is a good case to control that flow on the basis of skills and whether or not they're needed in Australia.

Coalition MP Andrew Laming rather contributed to the notion of Pacific Islanders being non-contributors in January 2013 when, in response to street brawls between Aboriginal and Pacific Islander young men in Logan, he tweeted 'Mobs tearing up Logan. Did any of them do a day's work today, or was it business as usual and welfare on tap?'. The irony, of course, is that for most young Pacific Islanders who have arrived in Australia since February 2001, welfare is not available at all.

Nor is a student loan. An emotional Tertiary Education Minister Craig Emerson announced before a gathering of Pacific Island school students in June 2013 that the Government would change the law to enable young Pacific Islanders who had arrived from New Zealand to get a loan to study. That he made the announcement of a policy affecting any young New Zealanders to such an audience perhaps shows who he felt was most affected by the exclusion (which remains in place today after the failure to pass any amending legislation). The then Government's publicity at the time also signalled it as a policy that would benefit Pacific Islanders. [Limited access to HELP loans was granted from 1 January 2016].

In recent years New Zealand politicians have mounted varying degrees of pressure on their Australian counterparts to reverse aspects of the 2001 changes. Asked in April 2013 why she had not repealed them, Prime Minister Julia Gillard said that:

“There were some issues when former Prime Minister John Howard and former Prime Minister Helen Clark entered into that agreement. We think many of those issues would still be relevant to considerations about repealing that agreement and repealing that legislation[.]”

Gillard did not spell out what these issues might be, but her vagueness invites the speculation that the ease of entry of Pacific Islanders to New Zealand may still be a key factor. In December 2000 Clark had felt that the only real difference in the immigration policies of the two countries was the entry right for 1,100 Samoans annually, but New Zealand's close relationship with the Pacific would not change. Others suspect this remains the sticking point. Aussie Malcolm said in April 2013:

“Now what outstanding issues might there be that could possibly worry Australia?… Can you identify any place where New Zealand immigration policy is significantly different to Australia's? Yes you can - Cook Islands, Niue and the Samoan quota. That is what it's all about.”

Phil Goff, New Zealand's Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time of the 2001 changes, said in April 2013 that the numbers of Cook Islanders, Niueans and Tokelauans were so small that they could not reasonably worry the Australians. But he did concede that Australia 'might worry a little more about the 1,100 quota from Samoa'. A further suggestion that Australia has a concern about the very fact of New Zealand's arrangements with Pacific countries, rather than the actual numbers, came in 2012 when the Productivity Commissions of the two countries reported on 'Strengthening Trans-Tasman Economic Relations'. In their discussion draft the commissions made the following observation, which was presumably authored principally by the Australian side:

“in the trans-Tasman context, equal treatment [of migrants in each other's countries] could only be implemented if there were effectively full alignment of the two countries' migration and citizenship programs with respect to nationals from third countries… While both countries' arrangements emphasise skilled migration, there remain distinct differences between their immigration policies. In particular, New Zealand has a Samoan quota and the Pacific Access Category (where Samoan citizens and people from Kiribati, Tuvalu and Tonga are invited to apply for residence under these schemes).”

In October 2013 Ruddock, by now back in government, remained of the view that New Zealand's immigration relationship with the Pacific is a discriminatory measure in itself, and something that runs counter to his hope for a common border policy. As he put it, I would have liked to have seen New Zealand using similar criteria to us… I would like to think that we had a common border - but a common border would mean there had to be some changes.

The implication of this would appear to be that New Zealand's relationships with the island territories whose people are New Zealand citizens by birth, with the countries contributing migrants under the Pacific Access Category, and with Samoa in terms of the annual quota, are concessions that do not sit comfortably with Australia's desire for a non-discriminatory immigration programme. Ruddock suggested that the history of the White Australia policy had heightened the need for Australia today to 'put in place migration programmes that were non-discriminatory in terms of race, religion, culture, country of origin'. New Zealand, by contrast, he said, has 'had discriminatory measures. If you want to come from Samoa or Niue you come on a concessional basis'.

The suspicion remains that one reason for the maintenance of the 2001 changes is Australia's unhappiness about receiving Pacific migrants who would not otherwise be able to access Australia. Only last year Australian Treasurer Joe Hockey was asked on TV3's political affairs show The Nation 'Is this policy actually not about blocking New Zealanders coming into Australia, but is it a means of stopping citizens from other places, like Pacific Island migrants, coming to Australia through New Zealand?' Hockey replied that Australia was 'a very welcoming nation for people from the Pacific Islands'.

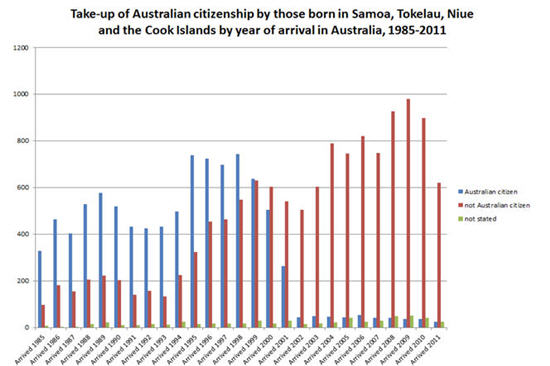

But if we look at this graph we can see that the opportunities for Pacific peoples to become Australian citizens, indicated by the blue bars, have all but evaporated since 2001. The door may be open, but the welcome mat is gone.

Read the National Library of New Zealand article.

Paul Hamer is a Wellington historian and a research associate at Victoria University's School of Māori Studies, Te Kawa a Māui.

Disclaimer

Paul is not an employee of the National Library, and as such his ideas and opinions are his own. This talk is an abbreviated version of an article previously published in Political Science, 66(2), 2014.